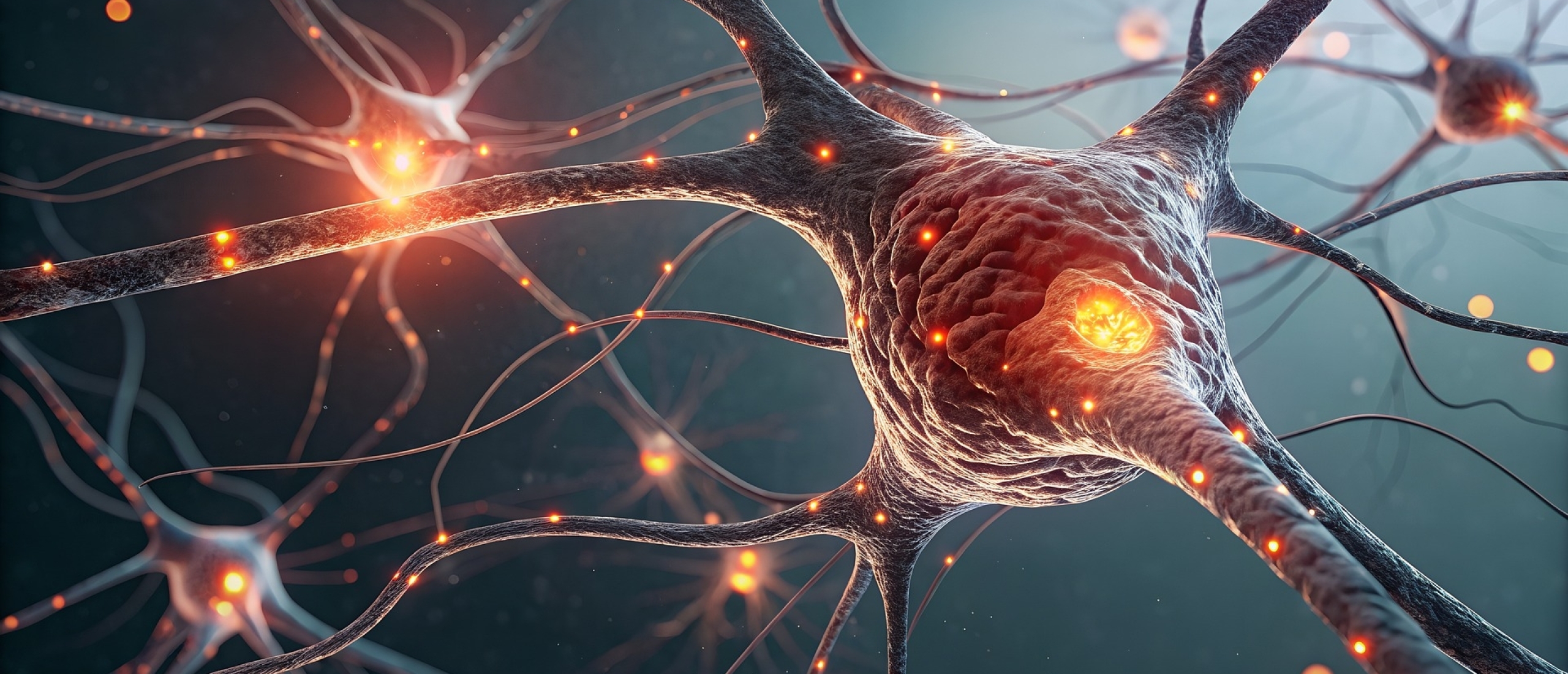

The Stressed Brain Doesn’t Just React — It Adapts: What Neuroscience Reveals About Chronic Stress

Most people think of stress as tension — worry, pressure, or overwhelm. But biologically, stress is a state of neural adaptation. Your brain does not simply “react” to chronic stress; it reshapes itself in response to the environment it believes you live in.

Acute stress is about immediate survival. Chronic stress is about long-term calibration: adjusting your brain’s circuitry so you can function in what it interprets as a consistently harsh, unpredictable world.

This has profound consequences.

Under chronic stress, the amygdala grows more sensitive, the prefrontal cortex becomes less effective at regulation, hippocampal circuits weaken, and the stress system itself becomes harder to shut down. These changes are not random damage — they follow a clear logic rooted in survival biology, allostasis (the process by which the body maintains stability through change), and evolutionary trade-offs.

These adaptations kept our ancestors alive in dangerous environments, but they come at a cost. In modern life, where stressors are chronic but rarely life-threatening, these same mechanisms become maladaptive and produce the symptoms people feel: irritability, cognitive fog, emotional overload, exhaustion, and a sense of being constantly “on.”

Understanding these processes explains not only why chronic stress feels so different from momentary pressure — but also why complete recovery takes weeks to months, not hours or days.

Key Takeaways

- Chronic stress creates predictable changes across brain systems, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus, and brainstem.

- These changes follow an evolutionary logic: in dangerous environments, a hypervigilant, fast-reacting, energy-conserving brain improves short-term survival.

- This process, known as allostasis, helps the brain maintain stability by adjusting neural circuits to environmental demands.

- When stress is prolonged without real danger, these adaptations accumulate into allostatic load, producing fatigue, cognitive decline, and emotional dysregulation.

- Chronic stress strengthens threat circuits while weakening regulation circuits through synaptic changes, dendritic remodeling, altered connectivity, and reduced BDNF.

- Recovery is possible — but slow — because the brain must be recalibrated through repeated experiences of safety, control, and predictability.

- Quick techniques calm acute stress, but long-term neural restructuring requires consistent changes in workload, environment, and recovery patterns.

Acute Stress vs. Chronic Stress: Two Different Biological States

Acute stress triggers two fast-reacting systems:

- The sympathetic–noradrenergic system, centred in the locus coeruleus, which releases noradrenaline and boosts arousal.

- The HPA axis, leading to cortisol release, which helps mobilise energy.

When these systems activate briefly, they improve performance.

When activation becomes continuous, the brain adapts structurally and functionally — not to help you thrive, but to help you survive.

Chronic stress is therefore not increased acute stress.

It is a different neural state with its own architecture.

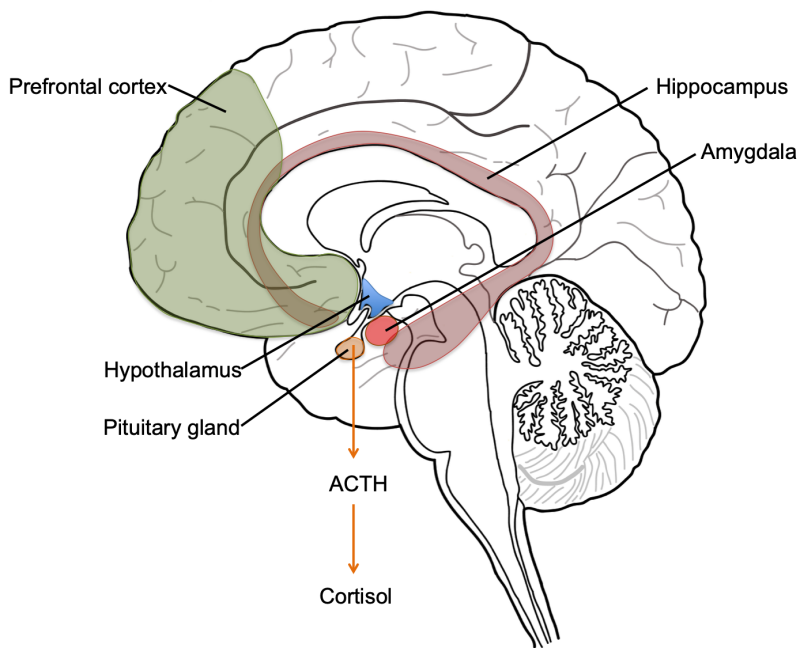

Diagram of the human brain with the prefrontal cortex (green), amygdala (red) and hippocampus (brown) highlighted. Chronic stress alters the structure and activity of these brain regions, and these changes can reverse given enough recovery time. Also indicated is the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, with the hypothalamus in blue and the pituitary in orange. The pituitary secretes the stress hormone ACTH, which will then activate the production and release of the stress hormone cortisol by the adrenal glands.

Diagram of the human brain with the prefrontal cortex (green), amygdala (red) and hippocampus (brown) highlighted. Chronic stress alters the structure and activity of these brain regions, and these changes can reverse given enough recovery time. Also indicated is the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, with the hypothalamus in blue and the pituitary in orange. The pituitary secretes the stress hormone ACTH, which will then activate the production and release of the stress hormone cortisol by the adrenal glands.

The Amygdala: Strengthening the Alarm System

The amygdala detects threat and coordinates rapid defensive reactions. Under chronic stress, two major changes occur:

1. Increased noradrenaline → heightened sensitivity

Persistent noradrenaline release makes amygdala neurons fire more easily. This amplifies:

- sensitivity to ambiguous cues

- emotional reactivity

- attention to threat-related information

2. Dendritic growth → stronger threat circuits

Studies show chronic stress leads to:

- expansion of dendritic branches

- increased spine density

- strengthened synaptic connections

This is the opposite of what happens in the prefrontal cortex (see below).

Result:

A brain that reacts fast — but not necessarily accurately.

The Prefrontal Cortex: Reduced Regulation and Control

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) handles:

- planning

- prioritising

- impulse control

- decision-making

- emotional regulation

Chronic stress weakens these functions through:

1. Synaptic weakening

Stress hormones impair:

- glutamate signalling

- working memory circuits

- sustained firing patterns

2. Dendritic retraction

Under persistent stress, PFC dendrites shrink and spines are lost. This reduces network integration and top-down control.

3. Functional consequence

The PFC becomes slower and less effective at:

- controlling emotional impulses

- regulating the amygdala

- organising complex tasks

- shifting attention flexibly

- making of decisions

This is why chronic stress snowballs into overwhelm and indecision.

The Hippocampus: Weakened Context, Memory, and Stress-Modulation

The hippocampus:

- provides context (“Is this situation actually dangerous?”)

- distinguishes past threat from present safety

- helps regulate the HPA axis

- supports memory formation

Chronic stress weakens hippocampal functioning through:

- reduced dendritic complexity

- decreased spine density

- impaired context encoding

- reduced inhibition of the stress response

This contributes to cognitive fog, overgeneralisation of fear, and difficulty “switching off”.

Stress Disrupts Connectivity Across the Brain

Chronic stress alters communication between key regions:

1. Amygdala–PFC pathway weakens

The amygdala becomes harder to regulate.

2. Amygdala–hippocampus pathway shifts

Emotional memories dominate over contextual information.

3. Hypothalamus and brainstem gain influence

Control shifts from slow, reflective processing to fast, reflexive survival circuits.

These network-level changes explain why chronic stress affects nearly every aspect of mental life.

Why the Brain Adapts This Way: The Survival Logic of Chronic Stress

The central question is:

Why does the brain remodel itself in exactly these ways under chronic stress?

Because evolution shaped the stress system to optimise short-term survival — not daily comfort.

In dangerous, unpredictable environments:

- Hypervigilance increases detection of threats.

- Fast reactions prevent costly hesitation.

- Cautious interpretation of ambiguous cues avoids deadly mistakes.

- Simplified cognitive processing conserves energy.

- Suppression of long-term biological processes reallocates resources to immediate survival.

In other words:

A chronically stressed brain is a brain preparing for life in a dangerous world.

This adaptation only becomes maladaptive in modern life, where stressors are persistent but not life-threatening.

When the brain believes it lives in danger — because stress signals never cease — it reorganises itself for survival.

This is allostasis: stability through change.

Allostasis vs. Allostatic Load

Allostasis is the process of using neural and hormonal changes to maintain stability under stress.

But this comes with a cost.

When adaptation is prolonged, the cumulative wear and tear is called allostatic load, which leads to:

- fatigue

- irritability

- reduced cognitive capacity

- metabolic problems

- difficulty recovering

- vulnerability to burnout

The same mechanisms that once improved survival now create decline.

Cortisol, Noradrenaline, and BDNF: The Core Molecular Drivers

Cortisol

Chronic cortisol exposure alters receptor sensitivity and disrupts synaptic plasticity in the PFC and hippocampus.

Noradrenaline

Persistent noradrenaline keeps the brain in hyperarousal, heightening emotional reactivity and strengthening fear-based learning.

BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor)

BDNF supports:

- dendritic maintenance

- synaptic resilience

- healthy plasticity

Chronic stress suppresses BDNF, leaving neurons more vulnerable to structural change.

Why Chronic Stress Feels So Bad

Because each neural change maps directly to subjective experience:

- Hypervigilant amygdala → irritability, anxiety

- Weakened PFC → overwhelm, indecision, rumination

- Impaired hippocampus → cognitive fog, memory problems

- Altered networks → difficulty switching off

- Chronic noradrenaline → tension, restlessness

- Allostatic load → exhaustion

These are not failures of character.

They are normal consequences of neural adaptation.

Recovery Takes Time — Because the Brain Must Recalibrate

Recovery is possible, but not fast.

Why?

Because recovery is not the opposite of stress.

Recovery is the brain learning that the world is no longer dangerous.

This requires:

- consistent reductions in uncontrollable stress

- repeated experiences of safety

- regained sense of control

- sustainable recovery periods

- stable routines

- supportive interactions

Only through repeated signals does the brain reallocate energy toward long-term maintenance and regrow dendritic structures and synaptic networks.

This process can take weeks to months, depending on the severity and duration of stress exposure.

Do Micro-Techniques Rewire the Brain Back to Calm?

Acute techniques (deep breathing, grounding, micro-pauses)

✔ reduce noradrenaline

✔ calm sympathetic arousal

✔ improve momentary PFC control

But:

✘ they do not reverse dendritic retraction

✘ they do not rebuild connectivity

✘ they do not recalibrate the brain’s internal model of the world

Long-term practices (mindfulness, CBT, structured relaxation)

When practiced consistently, and combined with changes to stress input, these can:

- reduce amygdala reactivity

- strengthen PFC–amygdala connectivity

- support BDNF upregulation

- stabilise network functioning

But they must occur in the context of a genuinely less overwhelming environment.

Recovery requires the brain to see a pattern of safety — not just moments of calm.

What Actually Rewires the Brain Back Toward Calm

The most promising scientific evidence suggests that recovery is supported by:

1. Reducing chronic stressors

Particularly uncontrollable ones.

2. Increasing sense of control

Even small increases in the sense of control restore PFC engagement.

3. Social buffering

Supportive interactions stabilise stress systems.

4. Regular recovery time

The brain needs off-duty periods to reorganise. Mental recovery requires intentional breaks that restore mental energy, regulate emotions, and help you regain clarity. This engages your prefrontal cortex.

5. Sleep

Integrates safety signals into long-term plasticity. And a good night's sleep helps to build resilience.

6. Physical activity

Potently increases BDNF and supports synaptic repair.

Recovery is a biological process — not simply a psychological one.

Your Next Step

Chronic stress doesn’t just exhaust you — it reshapes your brain.

But those changes are reversible with the right conditions.

If you want to understand how to reduce overload and restore a sense of control, download “Trapped in Overwhelm”.

FAQs

1. Are chronic stress changes permanent?

No. They are reversible, but recovery requires sustained changes, not quick fixes.

2. How long does recovery take?

Weeks for functional recovery; months for structural restoration.

3. Can micro-techniques fix chronic stress?

They calm acute stress but are not sufficient for long-term rewiring.

4. What triggers long-term recovery?

Reestablishing control, predictability, rest, and supportive environments.

5. Is chronic stress ever adaptive?

Yes — in dangerous environments. But in modern life, the costs outweigh the benefits.

References

- Vyas, A. et al. (2002). Chronic stress induces contrasting dendritic remodeling in hippocampal and amygdaloid neurons. J Neurosci.

- Roozendaal et al. (2009). Stress, memory and the amygdala. Nat Rev Neurosci.

- Arnsten, A. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci.

- Radley J. et al (2006)

- Repeated stress induces dendritic spine loss in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex

- Radley, J. et al. (2004). Stress alters dendritic spine morphology in PFC neurons. J Comp Neurol.

- McEwen, B. & Morrison, J. (2013). The brain on stress: Vulnerability and plasticity. Neuron

- Conrad, C. (2008). Chronic stress-induced hippocampal vulnerability. Rev Neurosci.

- Duman R.S. & Monteggia L.M. (2006) A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry.

- Rothman & Mattson (2013). Activity-dependent, stress-responsive BDNF signaling and the quest for optimal brain health and resilience throughout the lifespan. Neuroscience

- Radley, J. et al. (2005) Reversibility of apical dendritic retraction in the rat medial prefrontal cortex following repeated stress. Exp Neurol.

- Liston, C. et al. (2009). Psychosocial stress reversibly disrupts prefrontal processing and attentional control. PNAS.

- Hölzel, B. et al. (2009) Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci.

- McEwen, B. (1999). Stress and hippocampal plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci.

- McEwen, B. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci.