Introduction

On a quiet night shift, Officer Johnson pulls up to a domestic dispute. The air is thick with tension, the neighborhood silent except for the hum of his patrol car. Every call carries uncertainty — fear, adrenaline, and duty all at once. Moments later, the situation de-escalates; no one is hurt. Yet as Johnson drives away, his heart is still racing, and his mind replays the scene long after his shift ends.

Scenes like this capture the paradox of policing: a profession that is both thrilling and draining. For some, the adrenaline and sense of purpose create meaning and pride. For others, the emotional toll of repeated trauma, long hours, and organizational pressures slowly accumulate into chronic stress or burnout.

This article explores that complexity — the fine line between resilience and exhaustion — by examining data, causes, and cultural factors behind police and stress, and what can be done to protect mental health in law enforcement.

How Common Is Stress in Police Work?

Policing ranks among the world’s most psychologically demanding professions. Officers routinely face danger, human suffering, and public scrutiny — while maintaining composure and professionalism. Research shows just how widespread the effects are:

- In a survey of over 1,100 Portuguese officers, 88 % reported high operational stress and 87 % reported high organizational stress; 11 % were already in the “critical” range for burnout.

- Among 434 U.S. patrol officers, 26 % met criteria for a current mental-health condition (depression, anxiety, or PTSD).

- Studies consistently estimate PTSD prevalence between 12 – 35 %, depending on exposure level and country.

- Officers working night shifts are about four times more likely to report depressive symptoms than day-shift colleagues.

- In a national U.S. wellness survey, 83 % of officers said their mental health directly affects their performance, yet most never seek help.

A longitudinal study from the U.S. National Institute of Justice found that stress tends to rise sharply during the first 13 years of service, before gradually declining — possibly as officers adapt or transition to administrative roles. The data paint a clear picture: stress in policing is not an occasional hazard, but a chronic occupational reality.

As stress is thus common in police work, it is important to recognize the early signs of stress, so that you can take measures to reduce stress before it gets out of hand.

The Many Faces of Police Stress

Researchers often distinguish between operational, organizational, and personal sources of stress. Understanding these layers helps explain why some officers cope better than others.

1. Operational Stressors — The Frontline Burden

These are the most visible pressures:

- Exposure to violence, death, and suffering

- Responding to traumatic incidents such as accidents, suicides, or child abuse

- Split-second life-or-death decisions

- Shift work, sleep disruption, and irregular meals

- The ever-present threat of danger

These experiences activate the body’s stress system repeatedly. When recovery time is short, the biological “reset” never completes, leaving officers in a state of chronic physiological activation.

2. Organizational Stressors — The Hidden Weight

Paradoxically, what happens inside the department can be just as stressful as what happens on the streets.

Officers frequently cite:

- Excessive paperwork and bureaucracy

- Lack of control over schedules and decisions

- Inconsistent leadership or perceived injustice

- Limited resources and understaffing

- Conflicting demands between supervisors and public expectations

Several studies show that organizational stressors often predict burnout more strongly than exposure to trauma. When officers feel unsupported or treated unfairly, even manageable operational stress can become overwhelming.

3. Social and Cultural Stressors — The Image of the Uniform

Public criticism, intense media attention, and strained community relations add another layer. Many officers report feeling isolated or misunderstood, caught between political expectations and on-the-ground realities. Maintaining composure in a world that scrutinizes every action is mentally taxing.

The “Macho Culture” and the Stigma of Stress

Beyond external pressures, policing carries an internal one — a deep-rooted culture of stoicism.

Officers are trained to stay calm under fire, to suppress emotion, to “handle it.” Over time, this becomes an unwritten rule: showing stress can be seen as weakness.

Surveys reveal how powerful this belief remains:

- Over 90 % of officers acknowledge that mental-health struggles are stigmatized within policing.

- 73 % believe seeking counseling could harm their career.

- In the U.K., only 19 % of officers with stress symptoms ever seek professional help.

This “macho culture” — sometimes described as hyper-masculine, stoic, or emotionally suppressive — may protect short-term performance but undermines long-term resilience. When stress is hidden rather than processed, cortisol levels remain elevated, sleep quality deteriorates, and symptoms of chronic stress emerge: fatigue, irritability, emotional numbing, or depression.

Resilience does not mean “never affected.” It means recognizing and regulating stress before it becomes damage — a distinction many departments are now trying to teach through peer-support programs and mental-health training.

Why Some Officers Burn Out While Others Thrive

Not every officer exposed to the same stressors develops burnout. Individual differences, support systems, and work environments all matter.

Protective factors include:

- Strong sense of purpose and mission

- Supportive leadership and fair treatment (“organizational justice”)

- Positive team climate and peer support

- Emotional regulation skills and self-awareness

- Healthy recovery habits — sleep, exercise, decompression time

- Opportunities for autonomy and control over work

Officers who view challenges as meaningful and feel supported by colleagues often describe stress as energizing rather than draining — a form of eustress that enhances focus and purpose. Conversely, those facing chronic injustice, role conflict, or isolation are more prone to exhaustion and disengagement.

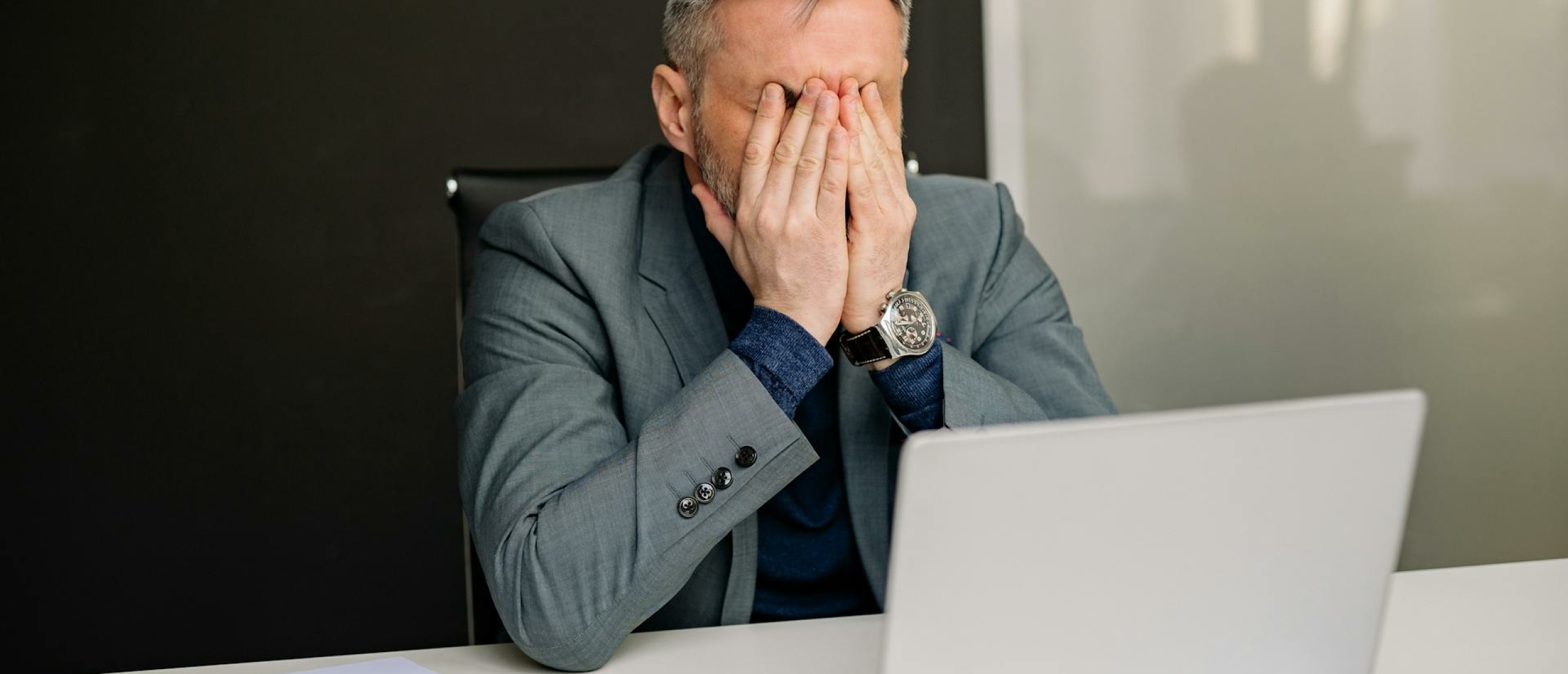

Consequences of Unmanaged Stress

Unchecked, chronic stress in policing can have cascading effects.

For individuals:

- Burnout, depression, anxiety, PTSD

- Cardiovascular disease and metabolic problems

- Substance use, insomnia, irritability, or aggression

- Relationship strain and family breakdown

- Increased risk of suicide — estimated to be higher among police than in the general population

For organizations and society:

- Reduced concentration and slower reaction times

- Errors in judgment and excessive use of force

- Higher absenteeism and turnover

- Decline in morale and team cohesion

- Erosion of public trust and community relations

The cost is not only human but also institutional: replacing an experienced officer can exceed $100,000, while losing community confidence is immeasurable.

Pathways to Recovery and Resilience

Because stress in policing has multiple roots, solutions must act on several levels.

1. Individual-Level Strategies

- Develop stress awareness and early-warning signs.

- Practice brief decompression techniques between shifts (controlled breathing, mindfulness, exercise).

- Prioritize recovery: consistent sleep, nutrition, and social contact.

- Maintain boundaries — consciously “leave work at work.”

- Seek confidential peer or professional counseling when needed.

2. Organizational Interventions

- Train leaders in psychological safety and fair treatment.

- Streamline bureaucracy; ensure adequate staffing.

- Rotate assignments to avoid prolonged exposure to trauma.

- Offer confidential mental-health services without career penalties.

- Encourage peer-support teams and post-incident debriefings.

Evidence suggests that organizational justice — feeling valued and treated fairly — is one of the strongest predictors of resilience and engagement among officers.

3. Cultural Transformation

- Redefine strength: not “never breaking,” but “knowing when to reach out.”

- Include mental-health education in police academies.

- Highlight role models who speak openly about their experiences.

- Measure wellness, not only performance.

- Foster collaboration with psychologists and community partners.

Conclusion

Policing is a profession of paradoxes — courage and vulnerability, duty and doubt, adrenaline and exhaustion. The science is clear: stress in police officers is not inevitable, but it is cumulative and multifactorial.

Acknowledging it is not weakness; it’s a first step toward sustainability.

As departments modernize and cultures evolve, resilience will depend less on silence and more on openness — turning the badge from a symbol of stoicism into one of balance and humanity.

If you’re working in a high-stress profession and recognize some of these signs in yourself, you can take our free Work Stress Self-Test or download the ebook “Trapped in Overwhelm", with five micro-actions you can directly apply to reduce your stress.

Small steps toward awareness can prevent big consequences later.

Sources

- Queirós, C. et al. (2020). Stress, burnout and coping in police officers: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 587.

- Violanti, J. M. et al. (2020). Police stressors and health: A state-of-the-art review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6718.

- Stinchcomb, J. B. (2004). Searching for stress in all the wrong places: Combating chronic organizational stressors in policing. Police Practice and Research, 5(3), 259–277.

- McCreary, D. R., & Thompson, M. M. (2006). Development of two reliable and valid measures of stressors in policing. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(4), 494–518.

- Violanti, J. M., & Aron, F. (1995). Police stressors: Variations in perception among police personnel. Journal of Criminal Justice, 23(3), 287–294.

- National Institute of Justice (2012). Stress Patterns in Police Work: A Longitudinal Study. U.S. Department of Justice.

- Andersen, J. P. et al. (2015). Police stress and performance: Findings from the Buffalo Cardio-Metabolic Occupational Police Stress Study. BMJ Open, 5(10): e008276.

- Karaffa, K. M. et al. (2020). Stigma and mental health service use among police officers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47(3), 272–289.

- Police1 (2024). What Cops Want: The Police Wellness Crisis — New Research and Recommendations. Retrieved 2025 from police1.com.

- Police Federation of England and Wales (2021). Demand, Capacity and Welfare Survey.

- Violanti, J. M., & Owens, S. L. (2021). Police culture, stress, and health. In Handbook of Policing and Society. Routledge.

- Brough, P., & Frame, R. (2004). Predicting police job satisfaction: The role of organizational variables, stress, and coping. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 6(1), 12–32.